Public and private security leaders at all levels have one thing in common: They seek to identify those not adhering to their environment’s established behavioral expectations. And if the reasons or motives for those behaviors can be identified, so much the better. Whether a person works in an industry that formally relies on such methods or is a security novice, we all conduct similar assessments as we go about our daily business. We consciously and unconsciously compare the behavioral information we perceive against our definitions of what is “normal,” simultaneously relying on the context of our environment and past experiences as a baseline for our conclusions. These behavioral data points can all be labeled as expressions.

An early master of identifying and assessing expressions was former New York Police Department (NYPD) Detective Bo Dietl. His ability to use a variety of seemingly meaningless or unrelated clues (“expressions”) to quickly assess the likelihood of criminal behavior was legendary. Throughout his career, Dietl’s uncanny abilities led to more than 1,400 felony arrests and 60 awards from the NYPD. Fortunately, we don’t all have to have Bo Dietl’s experience, skillset, or deliberate nature in conducting this analysis to make the same decisions. Whether formally or informally, we generally categorize the people in our environment as one of the following: Acceptable, Adversarial, Anonymous, or Anomaly. In essence, we determine what the sum of someone’s expressions means to us in terms of our security. In many cases, the analysis concludes quickly. Someone is either a potential friend (Acceptable), a potential foe (Adversarial), neither friend nor foe (Anonymous), or we don’t have enough information to make a clear decision (Anomaly). In years past, seeking out, identifying, and assessing data in a given environment was referred to as “exception-based reporting.” While that phrase may have been replaced with terms more in vogue, such as “risk analysis, threat assessment, insider threat, or threat hunter,” the related security activities are anything but obsolete.

Cyber threat hunters, technological advancements, and the ability to identify actions or communications that breach behavioral standards have also seen a significant uptick in activity and interest, and a plethora of information is available. Those clues may appear in a variety of expressions which can include:

- Web sites visited

- Internet purchases

- Social media accounts

- Email accounts

- Alias accounts

- IP addresses (including the use of proxy servers)

- Chat rooms entered, chats

- Texts, or digital messages

- Words used or repeated in emails, texts, or phrases in digital communications

- Digital files stored, shared, transferred, uploaded, downloaded, or deleted

- Activity detected by video systems or reported by a video analytics system

- Access card transaction history

- Data from license plate readers

- Phone records

Information about where one has been, when they were there, what behaviors or communications they engaged in, and how often a location was frequented could add helpful information to an assessment. On the behavioral side, common investigative angles include:

- Work and military history

- Criminal and mental health history

- Credit history and credit card purchases history

- Behaviors or communications reported by third parties (family, friends, co-workers, associates)

- Postings on social media or other forms of written communication

- A change from previous behavioral or communication styles

- Stressful events (relationship difficulties, death, serious or chronic injury or pain, debt, job loss, etc.)

- Acts of aggression or violence

- Substance abuse or other addictive behaviors

- Acquisition, or increased interest in weapons, or interest in violence or terrorist groups

While behavioral and cyber experts collect, filter, and analyze data, the underlying reasons for their investigative activities are essentially the same. As cyber experts identify and decipher digital clues, behavioral specialists search to uncover activities that provide insight into a person’s intentions or motives. Though often working independently, both groups of experts are looking for expressions. Whether those expressions are identified and collected in the digital world or the physical world, information from both domains constitutes an integral piece of a larger puzzle, the risk or threat assessment. To the extent that any given expression provides context, dimension, or depth to evaluate risk or threat further, their value remains equally balanced.

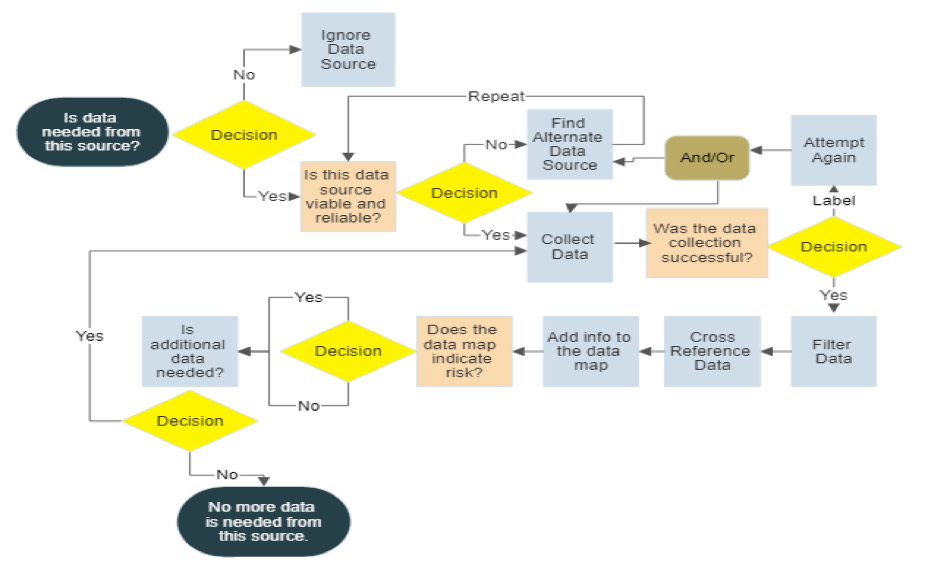

But everything comes with a price. In today’s world, there is greater and easier access to clues that someone may be violating (or contemplating violation of) behavioral standards. The sheer volume of information available to the assessor can sometimes be so staggering that the collection, filtration, and analysis are quite cumbersome. Therefore, it’s important to have a standardized approach to the process. Below is a generalized design for a data collection plan that could be applied to each data source under consideration.

When considering your options for sources of expressions, you may find it efficient to compile a prioritized list of data points with the most probative value to your analysis. For example, when examining physical expressions, any or all of the following have importance: verbal and non-verbal communication, including gestures and facial expressions as well as macro and micro-expressions, reticence (when some form of communication would typically be expected), writings, postings, photos, videos, presence of an individual when or where they are not expected to appear or the converse (absence of an individual when or where they are expected to appear), statements offered by individuals known to the person of interest (these may help establish a baseline for behaviors and communications typically demonstrated as well as behaviors or communications which represent changes to those baselines), behavioral history in all available forms (work, health, social, etc.), and photos or videos, especially those in which the person of interest is depicted or where they may have added comments.

Digital expressions, though potentially more abundant, will require access to the communication devices (phones, laptops, tablets, etc.) which send, receive, or store the data being sought. Consequently, there will be an increased reliance on tools that can be used to gain access to the information on those devices. If, however, the person of concern is using communications tools issued and owned by a third party (i.e., an employer), accessing and collecting data may be somewhat less complicated. In either case, it may be necessary to use software such as security incident and event management (SIEM), endpoint detection and response (EDR), extended detection and response (XDR), and cyber threat intelligence (CTI), including either commercial or privately developed applications. Other sources typically available in commercial environments may include access control and video (ACV) systems or video analytics (VA) systems. In addition, intrusion detection systems (IDS) may also be helpful. Finally, data forensics and incident response (DFIR) software may also need to be included on your list of tools to access and retrieve hidden or deleted files.

In any risk or threat investigation, the validity of the findings and the conclusions drawn by the authors of subsequent reports are buttressed by the type, variety, and volume of information collected and analyzed. Digital and behavioral expressions which raise a red flag are relatively easy to identify or document. But making an insightful assessment of those expressions is a more significant challenge. Therefore, an investigative strategy that considers and includes expressions in physical and digital environments is essential. The greater the volume of expressions that can be collected, compared, and examined, the better their overall context can be understood. That understanding helps create a sustainable and repeatable process of delivering precise analysis, conclusions, and recommendations.

Organizations seeking to identify and mitigate risk should contact AT-RISK International. AT-RISK is prepared to help by providing experienced and credentialed staff certified in the latest risk methodologies.

For more information or to discuss your security and behavioral threat mitigation needs, please contact a member of the AT-RISK International team.